Oregon, Washington, British Columbia

Wake of the Explorers Bicentennial Expedition of 1992

![]()

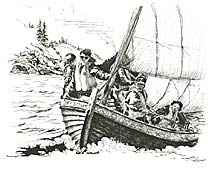

Watercolor, Pen and Ink - by Winifred Foster Martinson

Excerpts follow from Journal of Rediscovery, 1997, unfinished, by Gregory Foster.

Used by Permission. Brackets indicate breaks in excerpted material.

No temperate coastline on the face of the earth surrendered its cloak of mystery so hesitantly or late in time as the North Pacific shore of North America. As recently as two hundred years ago its true shape still eluded geographers striving to fill in the final blanks on the world atlas.

The Wake of the Explorers Bicentennial Expedition in 1992 was an adventure in reenacting history - learning and earning it firsthand -- not just through the dry pages of a book, but on the sometimes-wet wooden thwarts of open boats exactly similar to the ones that charted this coastline for the first time.

The Wake of the Explorers Bicentennial Expedition in 1992 was an adventure in reenacting history - learning and earning it firsthand -- not just through the dry pages of a book, but on the sometimes-wet wooden thwarts of open boats exactly similar to the ones that charted this coastline for the first time.

From May through September nearly 800 persons of all ages shipped aboard as working crew members on expeditions penetrating the remote inlets.

[And I was one of them. Gregory Foster is my brother.]

The incredibly detailed charts of the mainland coast which are the principal legacy of Vancouver's expedition would never have been possible if his chart makers had confined themselves to the two ships Discovery (ship-rigged sloop of war, 100 feet on deck, 330 tons burthen) and Chatham (armed brig, 60 feet on deck, 131 tons).

I n fact, it would have been an impossible mission but for the caliber of the captain, the superb skills of his mariners, assistance from friendly Natives along the way and the services of eight small open longboats. Indeed, the launches, cutters, yawl and jolly boats carried on the Discovery and Chatham, together with their counterparts from the Spanish explorations being conducted at the same time, are perhaps the real stars of the show. While the Mother ships groped their way up 2,000 miles of perilous seaboard in roughly linear fashion, the ships' longboats covered 10,000 miles exploring every nook and cranny of this challenging coast, virtually without mishap.

n fact, it would have been an impossible mission but for the caliber of the captain, the superb skills of his mariners, assistance from friendly Natives along the way and the services of eight small open longboats. Indeed, the launches, cutters, yawl and jolly boats carried on the Discovery and Chatham, together with their counterparts from the Spanish explorations being conducted at the same time, are perhaps the real stars of the show. While the Mother ships groped their way up 2,000 miles of perilous seaboard in roughly linear fashion, the ships' longboats covered 10,000 miles exploring every nook and cranny of this challenging coast, virtually without mishap.

The Wake of the Explorers Bicentennial Expedition in 1992, which took place in British Columbia, Washington and Oregon, for the first time acknowledged and celebrated these valiant little vessels which routinely were expected to sound uncharted channels ahead of the mother ship, tow her in calms, carry out and retrieve her numerous anchors, fill her water barrels, provision her larder, fetch firewood for her galley stoves, conduct charting and fishing expeditions, and in the event of shipwreck or men overboard be called on for lifesaving duty.

Did I mention that all of these craft were built by quiet, traditional hand tool methods, out of respect for the original shipwrights? This was undoubtedly the most fascinating aspect for the visitors who flocked to these exhibition workshops to watch the beautiful curves of the old longboats emerging under the ministrations of handsaws, bowsaws, drawknives, spokeshaves, adzes, chisels, planes, breastdrills, augers, hammers and mallets, simple tools of prehistoric shape, still as effective in skilled hands as they ever were.

Few of the crew members [of the reenactment] had any experience with old fashioned boats and their antiquated gear. Some had never rowed or sailed before. None knew what to expect. Nevertheless they had signed on with alacrity. None of us was accustomed to such fatiguing labour, straining at the heavy oars all day long, pulling for all we were worth at each and every stroke, keeping our mouths shut about the burning blisters on our hands [and bottoms], trying to stay in unison and getting crosser whenever the oars clashed, hour after weary hour fighting the wind and rain as we struggled ever deeper into the awesome heart of mystery. We were out of our normal depth and shut off from our familiar worlds, trying to follow the everlasting shadows of Vancouver's longboats somewhere up ahead.

Few of the crew members [of the reenactment] had any experience with old fashioned boats and their antiquated gear. Some had never rowed or sailed before. None knew what to expect. Nevertheless they had signed on with alacrity. None of us was accustomed to such fatiguing labour, straining at the heavy oars all day long, pulling for all we were worth at each and every stroke, keeping our mouths shut about the burning blisters on our hands [and bottoms], trying to stay in unison and getting crosser whenever the oars clashed, hour after weary hour fighting the wind and rain as we struggled ever deeper into the awesome heart of mystery. We were out of our normal depth and shut off from our familiar worlds, trying to follow the everlasting shadows of Vancouver's longboats somewhere up ahead.

When the planked boats of the explorers encountered the dugout canoes of the Coast Indians, two of the world's most important watercraft traditions met face to face in their heyday, and the splash of the oar and the dip of the paddle have persisted as another basic rhythm - like the tides - in the music of these waters ever since.

[The Elizabeth Bonaventure, and the Niña, were designed and built by my brother in his coastal B.C. Historic Watercraft Boatyard. The EB was a 26-foot replica of Captain Vancouver's yawl from the Discovery, rowing eight oars double-banked and sailing with a three-masted dipping lugsail rig. The 23-foot lancha Niña with her carved sheer and pine-tarred planking also rowed eight oars, and carried a two-masted (schooner) dipping lugsail rig. Almost 20 other replicas were being produced in many NW coastal communities including three built in an improvised street-front boatshop at the Oregon Historical Society in the heart of downtown Portland. The EB and the Niña are featured in my Ships' Boats Series in both watercolor and pen and ink and were originally made to illustrate Greg's Journal. The drawings were my very first attempt at pen and ink work.

My own memories of that summer with history-minded adventurers, and my artwork since, reflect an appreciation of the metaphor of rediscovery, which seems to me to provide the restorative means of finding our way in this fragile and abundant land.]

--Winifred Foster Martinson